Member/Partner News

Photovoltaic Myths

Alejandro Labanda, Head of Regulation and Studies, UNEF

Paradoxically, at a time when there is more interest in learning about renewables and the energy transition, some false myths are spreading and taking root more quickly. The desire of those of us in the sector to use narratives that are easy to understand should not be to the detriment of providing a vision based on data, which avoids the formation of mental frameworks that are not an appropriate representation of reality.

In the first of a two-part series of articles, we are going to look at three false myths about the development of photovoltaic installations, which have entered strongly into the imaginary of the sector. As false myths, they serve and fit well in common narratives, but they fall apart when contrasted with data.

Not all photovoltaic plants are macro plants

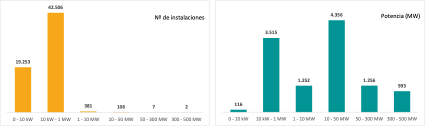

We start with one of the most recent ones, as, apparently, the projects of new photovoltaic plants in Spain have disappeared, now there are only macro plants. The reality is that plants with a power of 50 MW or less are still the most common.

If we look at the existing plants, according to data from the register of installations (PRETOR) we see that the bulk of installed photovoltaic power is in plants of less than 50 MW. In fact, up to 38% of the installed PV capacity is provided by plants between 10 MW and 50 MW. There are only 9 plants larger than 50 MW in Spain, which account for 2,249 MW, 20% of the installed capacity, and among them, there are only 2 plants larger than 300 MW.

If we look at new developments, although this information is not centralized, something similar happens. First, it should be known that projects of less than 50 MW are processed through the Administration of the Autonomous Regions and those of more than 50 MW through the Ministry for the Ecological Transition (MITECO). Therefore, if we compare the data of projects being processed in one way and the other, we will have an approximation of this distribution for future plants.

Well, the MITECO responded in June 2020 to a request for a Report in the Senate indicating the renewable files in the pipeline (not yet authorized). In the list published by MITECO there were 24 photovoltaic projects. According to this, there are in Spain 24 of these large projects (larger than 50 MW, their average size was 238 MW) that add up to a power of 5.7 GW, which would

represent 19% of the capacity to be developed to comply with the National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC), assuming they are all built.

The question is, how much do these large projects represent compared to the total developed in Spain, i.e., how much do these projects represent compared to what is processed in all the Autonomous Communities. About this, it is enough to consult any autonomous community with good solar resource (Extremadura, Murcia, Andalusia, Castilla-La Mancha) that will surely have more photovoltaic capacity in the pipeline than MITECO.

For example, the Government of Extremadura reported in January 2020 that it had photovoltaic projects in the pipeline with a total capacity of 6.2 GW, plants that are necessarily less than 50 MW. And this is only one of the aforementioned Autonomous Communities. In short, also for new projects the capacity of plants below 50 MW far exceeds the capacity of large plants.

Not all projects with network access permits will be built

In another recent classic myth, the data on network access permits granted, which is three times the PNIEC targets, is often used as a sign of an industry that will build many more plants than necessary and that is following a never-ending developmentalist model. However, by the very nature of the project development process, it cannot be taken for granted that all this capacity with network access permits will be built.

Until now, the first step in the development of new plants has been the application for the network access permit, but subsequently the project can 'fall through' for numerous reasons: not obtaining the environmental authorization, not successfully passing the administrative authorization, not getting the terrains, or simply being discarded or postponed in favor of another more advantageous one.

In fact, since June 2020 following the publication of RD-law 23/2020 and the administrative milestones it introduced to the holders of network access permits, there have been withheld requests or rejections for more than 20 GW of PV plants permits. Likewise, next year 2022 it is expected that, once again, a significant part of the permits granted will be cancelled, as the projects will have to prove that they have obtained the Environmental Impact Statement, probably the most crucial element of the development.

The development of installations is not going to grow to infinity, in fact, the built capacity is in line with government’s targets set in the PNIEC

For more than two years now, access and connection permits for photovoltaic have been two or three times the PNIEC's photovoltaic target capacity figures. According to the myth of the over-dimensioned and developmentalist sector, in these years plants would also be built in two or three times what was planned by the government. Well, we know that this is not the case.

In addition to the difficulties of the development process described above and the managed milestones introduced by RD-law 23/2020, photovoltaic projects need to secure their financing. To do this they largely require a stable revenue stream, i.e. a framework or agreement that ensures a fixed price for the sale of their energy.

This can take the form of auctions, whereby the fixed price is determined by regulation or by a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA). A minority also assumes the entire price risk without ensuring a fixed value, only selling on the wholesale market (merchant projects). In any case, the construction of plants ultimately depends either on the introduction of specific regulatory instruments or on a market that responds to the laws of supply and demand. The construction of facilities cannot grow infinitely, since either the government would not call auctions or the private sector would not need more renewable energy through PPAs.

Regarding PV, 4.2 GW were built in 2019, very little more than the 3.9 GW that the government auctioned in 2017. In 2020, 2.6 GW of PV were built (in this case without auctions, only through PPAs and merchant as there were no auctions). This figure is, not by chance, very close to what is needed every year until 2030 to meet the PNIEC targets. Therefore, with the data of installations connected to the grid, it cannot be said that we are in a model of unlimited construction.

In this and subsequent years, figures similar to 2-3 GW of new capacity are expected, in line with the annualized target of the PNIEC. In fact, the auctions introduced by the government plan to award this scheme to about 1.5 GW of PV annually until 2025. The auctions held in January this year awarded 2 GW of PV, to be built by February 2023.

In conclusion, renewables in general and photovoltaics in particular are naturally attracting the attention of society, which wants to understand and learn about the energy transition and the economic and social dynamics that are taking place. This is a source of pride for our sector and shows that we have an informed and attentive society. Those of us who have a public voice must find the compromise to present narratives that are simple to understand for the general public while still giving a vision well based on data.

![Global Solar Council [logo]](/static/images/gsc-logo-horizontal.svg)